Demographic shift in motion

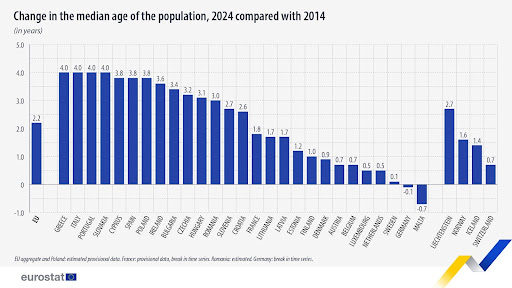

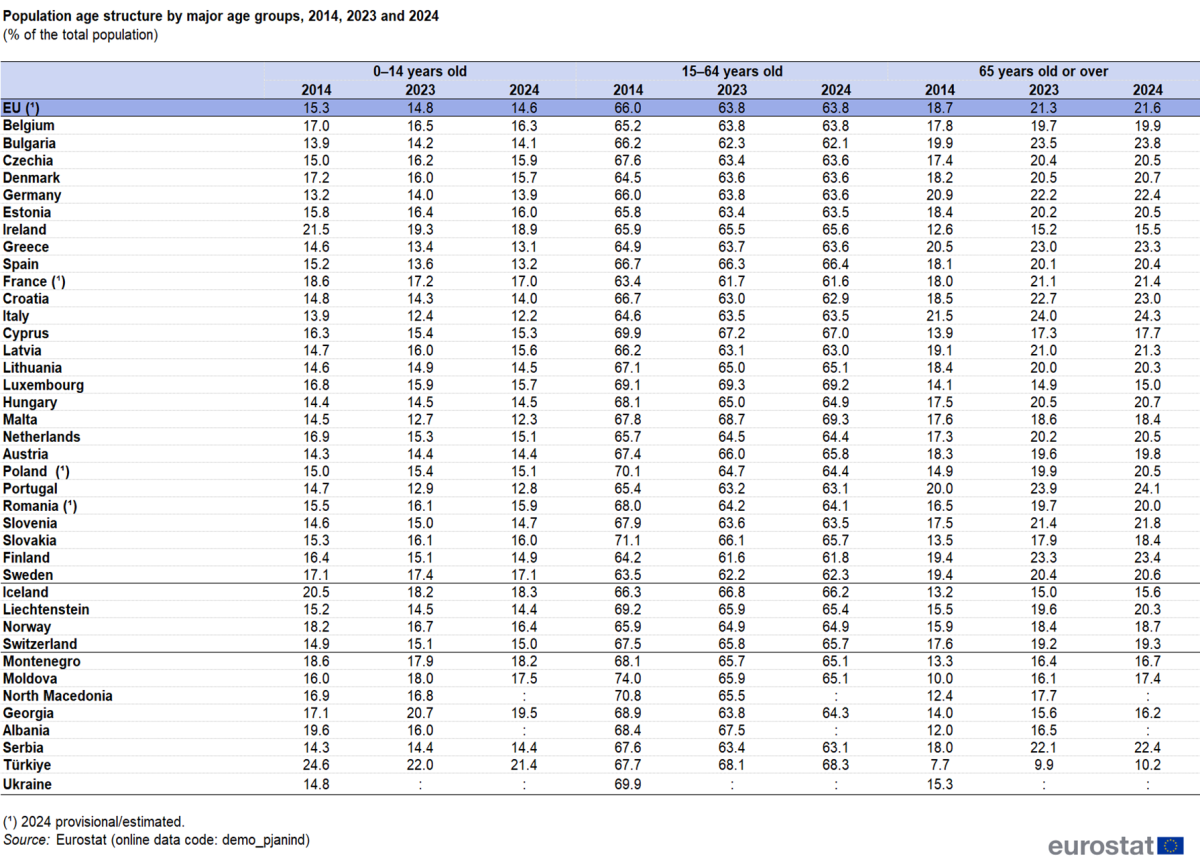

The proportion of older adults (65+) is rising across every EU country, reshaping the region’s demographic landscape. Over the past decade, this increase has been particularly pronounced in Central and Eastern Europe, where ageing populations are accelerating at an unprecedented pace.

Between 2014 and 2024, Poland (5.6 percentage points), Slovakia (4.9pp), Croatia (4.5pp), and Slovenia (4.3pp) experienced the most significant increases in their older populations. These countries, historically characterized by younger demographics, are now seeing a rapid shift due to a combination of rising life expectancy and declining birth rates.